Gereon Kopf from the Department of Religion at Luther College will be giving a talk entitled Meditation, Wisdom, and Compassion: A Zen Buddhist Vision of the Ecological Self for the theorizing at Rowan series on Wedenesday, February 26, at 10:50am in Westby Hall, Room 111.

Tuesday, February 25, 2014

Buddhism and Ecology Talk

There's a cool talk happening at Rowan on Wednesday morning:

Monday, February 24, 2014

I'm Certain I'm Doubting

Here are some links related to our discussion of knowledge and skepticism from class.

Here are some links related to our discussion of knowledge and skepticism from class.- What are the philosophical implications of the movie The Matrix?

- Here's a that cool article (pdf) on "live skepticism" we read for class. There's also an entire book on it.

- A few years ago, I interviewed the author of that book for the Owning Our Ignorance club. Here's the audio interview.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

audio,

cultural detritus,

knowledge,

links

Sunday, February 23, 2014

Test #1

Test #1 will be held at the beginning of class on Wednesday, February 26th. You will have about 25 minutes to take it. There will be a section on evaluating deductive arguments, and a section of short answer questions on the topics we discussed in class so far:

And a reminder: the first reading response is due Monday, February 24th.

- philosophy in general

- understanding and evaluating arguments

- types of arguments: deductive and abductive (inferences to the best explanation)

- what is knowledge?

- Plato's account of knowledge

- skepticism

- Descartes battling skepticism

And a reminder: the first reading response is due Monday, February 24th.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

knowledge,

logistics

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

We're All Skeptics Now

Here are some links related to our discussion of René Descartes and skepticism from class.

Optical illusion time! Here is a pair of collections

of Julian Beever's sidewalk art that looks three-dimensional when

viewed from a certain angle. That's a picture of one of his creations

above.

Optical illusion time! Here is a pair of collections

of Julian Beever's sidewalk art that looks three-dimensional when

viewed from a certain angle. That's a picture of one of his creations

above.- The search for truth is tough. Let's get the FBI on the case!

- Here's an audio interview about Descartes's famous argument that he's certain he exists.

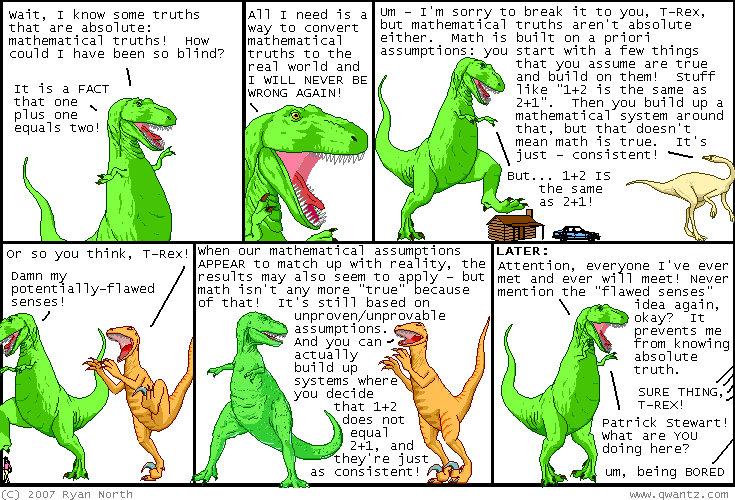

- Can we be abolutely certain of math claims like 2 + 3 = 5? This cartoon dinosaur says we can't.

By the way, if you have any links you think I or others in class might find interesting, let me know. And feel free to comment on any of these posts.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

comment begging,

knowledge,

links

Sunday, February 16, 2014

Do I Annoy You Because I'm a Jerk, or Am I a Jerk Because I Annoy You?

Socrates has a reputation of being a bit of a jerk. The following robot reenactment of one of his dialogues does little to dispel this reputation:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

knowledge,

links,

video

Saturday, February 15, 2014

K = JTB?

I wonder whether Plato would agree with T-Rex's analysis of knowledge:

In panel 5, Utahraptor is bringing up a Gettier case counterexample to the claim that knowledge = justified true belief that our textbook brings up.

In panel 5, Utahraptor is bringing up a Gettier case counterexample to the claim that knowledge = justified true belief that our textbook brings up.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

knowledge,

links

Thursday, February 13, 2014

Child Abduction

Psychologist Alison Gopnik gave a great TED talk recently on how children are natural abductive reasoners; playing and making pretend is often about coming up with and testing various hypotheses. Here's the talk:

Gopnik's book, The Philosophical Baby, is great.

Gopnik's book, The Philosophical Baby, is great.

Wednesday, February 12, 2014

Ockham Weeps

P.S. Remember when I was talking about Einstein's theory of general relativity having predictive power? This is what I had in mind.

Tuesday, February 11, 2014

Reading Response #1: Descartes

Reading Response #1 is due at the beginning of class on Wednesday, February 19th Monday, February 24th. In about a 500-word essay, answer the following questions:

Please paraphrase Descartes's ideas in your own words. The response is based on the Descartes reading from pages 207-216 of the textbook.

- What kinds of beliefs does Descartes say he cannot be certain of? Why does he believe he can't be certain of these?

- Hint: Descartes mentions 2 general categories of beliefs in Meditation I (pages 207-210). See also pages 159-160.

- What beliefs does Descartes say he can be certain of? Why does he believe he can be certain of these?

- Hint: Descartes mentions 2 specific beliefs in Meditation II (pages 210-216). See also pages 160-162.

- Evaluate his reasons: do you agree with Descartes? Why or why not?

Monday, February 10, 2014

Murder on the Abductive Express

Here's a paper that explains the importance of considering and testing multiple possible explanations rather than a single hypothesis:

I think abductive reasoning is the most effective tool we have when faced with the myriad uncertain, ambiguous issues and decisions that everyday life throws our way.

I think abductive reasoning is the most effective tool we have when faced with the myriad uncertain, ambiguous issues and decisions that everyday life throws our way.

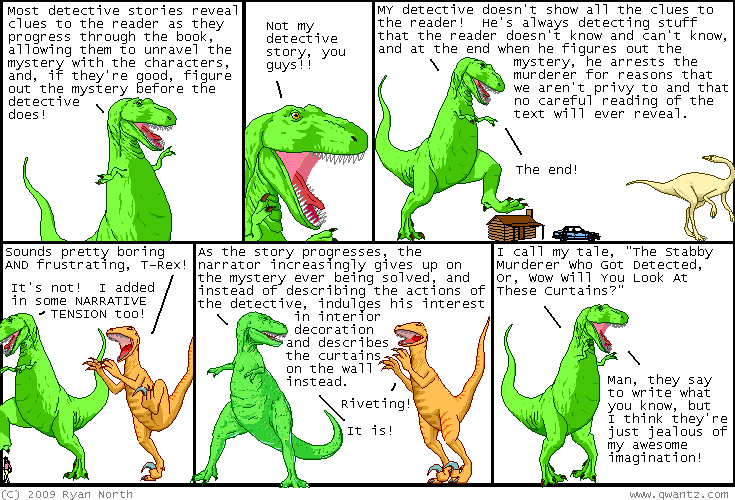

Lastly, here's a dinosaur comic murder mystery.

P.S. I'm 75% through reading this book: Inference to the Best Explanation by Peter Lipton.

Friday, February 7, 2014

An Argument's Support

One of the trickier concepts to understand in this course is the structure (or support) of an argument. This is a more detailed explanation of the term (it's the same as the handout). If you've been struggling to understand this term, the following might help you.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Deductive Arguments (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true for a deductive argument to have a good structure (to be valid). Notice we are only assuming the truth of the premises, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Deductive Arguments (Invalid)

An invalid deductive argument has a bad structure. You can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Deductive Arguments (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true for a deductive argument to have a good structure (to be valid). Notice we are only assuming the truth of the premises, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Deductive Arguments (Invalid)

An invalid deductive argument has a bad structure. You can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

Wednesday, February 5, 2014

Evaluating Deductive Arguments

Here are the answers to the handout on evaluating deductive arguments that we did as group work in class.

1) All bats are mammals.

All mamammals live on earth.

All bats live on earth.

All frogs are amphibians.

No frogs are humans.

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

Some Facebook posts are false.

Some annoying things are false.

Some people ate tacos yesterday.

Oprah Winfrey ate tacos yesterday.

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.

All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

12) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

1) All bats are mammals.

All mamammals live on earth.

All bats live on earth.

P1- true

P2- true

support- valid

overall- sound

2) Some dads have beards.

Some bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

Some bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

P1- true

P2- questionable ("mean" is subjective) or true ("Some" makes it easy to find one or two)

support- valid (the premises say the bearded dads will be mean)

overall- unsound (bad support)

3) All males in this class are humans.

All females in this class are humans.

All males in this class are females.

All females in this class are humans.

All males in this class are females.

P1- true4) No humans are amphibians.

P2- true

support- invalid (the premises only tell us that males and females both belong to the humans group; we don't know enough about the relationship between males and females from this)

overall- unsound (bad support)

All frogs are amphibians.

No frogs are humans.

P1- true5) All bats are mammals.

P2- true

support- valid(the premises say frogs belong to a group that humans can't belong to, so it follows that no frogs are humans)

overall- sound

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

P1- true6) All Facebook posts are annoying.

P2- true (if interpreted to mean "All bats are the sorts of creatures who have wings.") or false (if interpreted to mean "Each and every living bat has wings," since some bats are born without wings)

support- invalid (the premises only tell us one type of mammal has wings, not necessarily all mammals)

overall- unsound (bad support)

Some Facebook posts are false.

Some annoying things are false.

P1- questionable ("annoying" is subjective)7) Oprah Winfrey is a person.

P2- true

support- valid (the premises establish that some Facebook posts are both annoying and false; so some annoying things [those posts] are false)

overall - unsound (untrue first premise)

Some people ate tacos yesterday.

Oprah Winfrey ate tacos yesterday.

P1- true8) All students in here are mammals.

P2- true (you might not have directly seen anyone eat tacos, but you have a lot of indirect evidence... with all the Taco Bells, Don Pablos, etc., surely lots of people ate tacos yesterday)

support- invalid (the 2nd premise only says some ate tacos; Oprah could be one of the people who didn't)

overall- unsound (bad support)

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

P1- true

P2- true

support- invalid (the premises only tell us that students and humans both belong to the mammals group; we don't know enough about the relationship between students and humans from this; for instance, what if a dog were a student in our class?)

overall- unsound (bad support)

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

P1- true!

P2- true

P3- questionable ("scary" is subjective)

support- valid (same structure as in argument #1, just with an extra premise)

overall- unsound (untrue 3rd premise)

10) (from Stephen Colbert)

Bush was either a great president or the greatest president.

Bush wasn’t the greatest president.

Bush was a great president.

Bush was either a great president or the greatest president.

Bush wasn’t the greatest president.

Bush was a great president.

P1- questionable ("great" is subjective)

P2- questionable ("great" is subjective)

support- valid (it's either A or B; it's not A; so it's B)

overall- unsound (untrue premises)

11) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

P1- questionable (since you haven't heard me sing, you don't know whether it's true or false

P2- false

support- valid

overall- unsound (untrue premises)

12) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)

P2- true

support- invalid (from premise 1, we only know what happens when Sean is singing, not when he isn't singing; students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (untrue 1st premise and bad support)

13) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)

P2- false

structure- invalid (from premise 1, we only know that Sean singing is one way to guarantee that students cringe; just because they're cringing doesn't mean Sean's the one who caused it; again, students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (untrue premises and bad support)

14) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)

P2- true

structure- valid (the premises say Sean singing guarantees that students cringe; since we know students aren't cringing, we know Sean can't be singing)

overall- unsound (untrue 1st premise)

15) All students in here are humans.

Most humans are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Most students in here are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Most humans are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Most students in here are shorter than 7 feet tall.

P1- true

P2- true!

support- invalid (the premises state a strong statistical generalization over a large population, and the conclusion claims that this generalization holds for a much smaller portion of that population; while it could be true that the humans in here are a statistical anomaly, given the strength of the generalization, it's likely that most students in here are, in fact, shorter than 7 feet tall)

overall- unsound (not perfect, since the support isn't perfect, but pretty good)

16) If there is no God, then life is meaningless.

Life isn't meaningless.

There is a God.

Life isn't meaningless.

There is a God.

P1- questionable (that's not an obvious claim)

P2- questionable (again, that's not an obvious claim)

support- valid (the same structure as argument #13)

overall- unsound (untrue premises)

Saturday, February 1, 2014

Howard Sure Is a Duck

Howard the Duck is my favorite synecdoche for the 80's:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

video

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)